Universal Horror Classics: Comfort Food for the Senses (Part One)

PART ONE: GERMAN EXPRESSIONISM AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE HOUSE STYLE

With Jordan Peele’s Us breaking box office records for Universal this weekend, I thought it was time to revisit some Universal horror classics, those legendary chillers made between 1928 and 1960.

I’ve got a history of my own with Universal. I wrote and did research for Universal Television for a number of years. I worked in the publicity department, and one of the pleasures of the job was going into the archives and looking through the original 8×10 glossies and press kits of the classic horror films. To hold an original glossy of Bela Lugosi or Glenn Strange was such a thrill. I alao loved to wander around the backlot at lunchtime and stroll the European street where all of these classic monsters once walked.

Now that Svengoolie is showing them on Saturday nights, it’s rekindling happy memories of my youth, when I stayed up late to see Creature Feature on WSJV-TV in South Bend, Indiana.

Speaking of Svengoolie, when he showed House of Dracula recently, he noticed that the hunchbacked nurse’s hunch was rather strange looking, and cracked “Hey, here’s a tip. When you get implants, make sure they install them on the correct side.” I laughed for hours about that, because I remember even as a kid wondering why her hunch was so pointy.

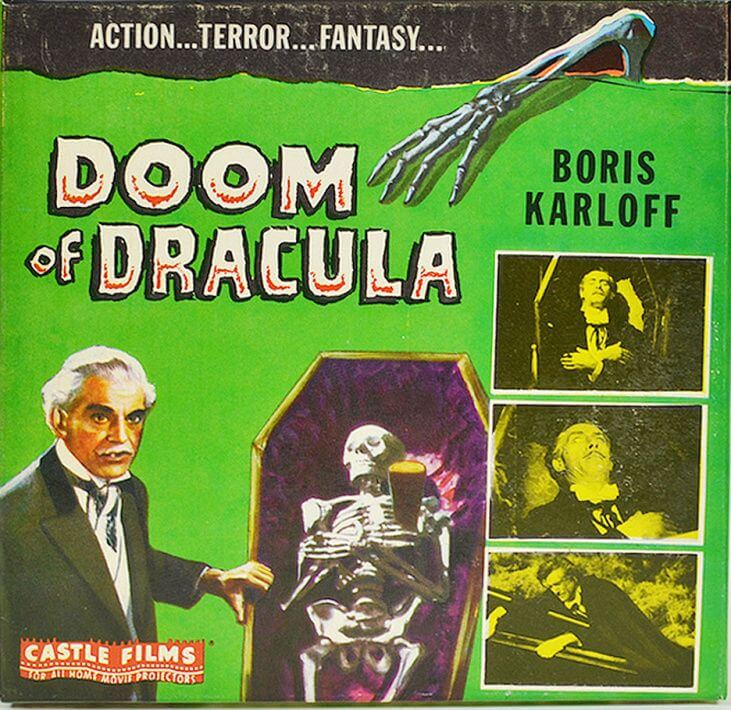

But, ah…the movies. It’s like getting back in touch with old friends after years of separation. Not that we’ve spent much time apart, though — I have Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein, The Invisible Man, Creature from the Black Lagoon (in 3D!), It Came from Outer Space (also in 3D) and Doom of Dracula on super 8mm film.

“What’s Doom of Dracula?” you may ask. Well, these films are all “condensations” — seven- to 17-minute excerpts of the features themselves, and Doom is the title of an excerpt which focuses on the Dracula segment in House of Frankenstein. They used to sell the full line of Castle Films at Kmart! This was long before the advent of home video, of course.

If you think these films would merely be a jumpy assortment of unrelated clips, you’d be sadly mistaken. Universal 8 (and its predecessor, Castle Films) put together really nice reels that stand on their own as entertainment. Sometimes they just focus on one segment (as in Doom), but others telescope the entire film into a comprehensible short subject, with all the famous scenes included. The quality was usually terrific, with the prints often having better contrast than the later releases on videotape!

Universal actually had not one but two golden ages of horror. The first was in the early-to-mid-1930s, when German filmmakers, fleeing the Nazis, were hired by the studio and brought along their Expressionist talents.

Even before the onset of sound, Paul Leni, one of the founders of the movement, directed two striking motion pictures: The Cat and the Canary (1927), an “old dark house” prototype; and The Man Who Laughs (1928), more of a period piece with nasty detail than a pure horror. This chiaroscuro look became the house style and made for some really beautiful filmmaking.

Other studios made horror films around this time, but they all seemed to be trying to jump on the Universal bandwagon. Paramount contributed a strong pre-Code Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, starring Fredric March, and its Island of Lost Souls (1932), starring Lugosi, is as close to a Universal film as it can be.Ironically, Universal bought all of Pramounts films made before 1948 and got Lost Souls, making people think it was always a Universal film.

Meanwhile, MGM nabbed Universal director Tod Browning for Freaks. With its sordid story and use of real circus “freaks,” it was rejected by the studio and doomed to travel the exploitation roadshow circuit until it was rediscovered in the 1960s.

Only Warner Bros., which represented the fast-talking, urban milieu of Jimmy Cagney and Edward G. Robinson, injected its own house style into its horror output, and Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933, Michael Curtiz) uses contemporary New York locales to full advantage. Shot in the primitive Technicolor, it is the first horror film with a modern setting. Check out the two-strip (red and green) Technicolor process:

But back to the Big U. Cinematographer Karl Freund, who worked on Lang’s Metropolis and Wegener’s Der Golem in Germany, helped to make films like Dracula (1931) and Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932) look so impressive. The shot of Lugosi as Dracula descending the staircase with the massive spiderweb behind it is unforgettable, even though the film itself is pretty creaky these days.

Its lack of a musical score (a snippet of “Swan Lake” is heard over the opening titles and that’s it) makes one realize how important a role music plays in genre pictures. George Melford directed a simultaneous Spanish-language version with different actors — a common practice at the time — and it’s considered to be more lively and sexy than the Lugosi version.

Freund directed a few movies himself, including The Mummy (1932), which certainly drips with atmosphere but I find boring. Sure, the make-up is good, but you only see it in the first few minutes. After that, it’s just Karloff in a fez trying to reunite with his long-lost Egyptian lover (Zita Johann). There is one great scene, though, and of course it’s at the beginning. When Egyptologist Norton (Bramwell Fletcher) is interrupted by the mummy coming to life and taking the ancient scroll he’d been trsanslating out of his hands, he reacts by bursting into hysterical laughter and exclaiming, “He went for a little walk!”

Edgar G. Ulmer’s The Black Cat, from 1934, starred the studio’s two top horror stars of the time — Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi — and really pushed the envelope (even though the Hays Code had been in force for four years). It featured devil worship, women entombed in glass cases and Bela skinning Boris alive. No fan of his English co-star, Lugosi must have enjoyed that.

The sets are a trip and still feel avant-garde today. It had nothing to do with the Edgar Allen Poe story, of course. It’s one of many, many films that have Poe titles but nothing else content-wise.

The epoch-making Frankenstein (1932) and its tongue-in-cheek sequel, 1935’s Bride of Frankenstein, established the mittel-European look that would carry through the 1940s with the monster rallies. It’s hard to believe that these two films were made by the same director. The first is grim and serious, while its sequel is one of the gayest horror films ever made.

The director, James Whale, was out and proud when such a thing was still considered an aberration.He didn’t really want to make the sequel, but Universal was so eager for him to do so that he finally acquiesced, although on his own terms.

Dr. Pretorius was played by the effete, skinny and bizarre (and flamboyantly homosexual) Ernest Thesiger. Karloff’s bride, Elsa Lanchester, was married to another flamboyantly gay actor, Charles Laughton. And it’s said that Henry Frankenstein himself, Colin Clive, was closeted and tormented by his sexuality, resulting in his descent into alcoholism and tragic death at age 37.

Keeping all this in mind while watching Bride makes it even more amusing. As the maid, the hysterical, birdlike Una O’Connor (also in Whale’s magnificent The Invisible Man) reluctantly admits Pretorius into the Frankenstein home, she looks him up and down suspiciously and you can just hear her thinking, “What’s the deal with this old queen?”

And when the monster goes to the cabin of the blind hermit (O.P. Heggie), there’s an outrageous double entendré that Whale must have intended. Karloff is supine on a bed and Heggie is kneeling next to him, thanking God for sending him a friend. But his head is lowered, and when Karloff gently strokes his shoulder, it looks for all the world like he’s being serviced!

Film scholars consider Frankenstein and Pretorius to be a couple, with Henry drawn to the older man in a Greek love sort of way. And who did the Bride’s styling? As Arthur Dignam, the actor playing Thesiger said in Bill Condon’s magnificent Whale biopic, Gods and Monsters (1998), “I gather we not only did her hair but dressed her. What a couple of queens we are, Colin!” Even the monster’s happiest relationship is with the hermit, whom he is willing to set up house with before the trouble starts.

When people think of the werewolf, their minds are automatically transported to Lon Chaney, Jr.’s tormented Larry Talbot in 1941’s The Wolf Man, but lycanthropy was explored in an earlier Universal film — 1935’s Werewolf of London starring Henry Hull. I actually prefer the latter one. The modern urban setting and Jack Pierce’s more subtle (but still effective) make-up was just more interesting to me than the fairytale world of the Chaney version, charming as it may be.

When people think of the werewolf, their minds are automatically transported to Lon Chaney, Jr.’s tormented Larry Talbot in 1941’s The Wolf Man, but lycanthropy was explored in an earlier Universal film — 1935’s Werewolf of London starring Henry Hull. I actually prefer the latter one. The modern urban setting and Jack Pierce’s more subtle (but still effective) make-up was just more interesting to me than the fairytale world of the Chaney version, charming as it may be.

And this is such a civilized werewolf! He puts on his hat, coat and scarf before he goes out for the evening. Unfortunately, the lack of star power (it was originally intended for Karloff and Lugosi) and similarity to the earlier Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde caused it to flop at the box office, but it has quietly generated a cult following over the years. And actress Valerie Hobson played two important brides that year — the werewolf’s and Henry Frankenstein’s.

1936 saw the release of Dracula’s Daughter starring Gloria Holden and Edward Van Sloan (playing Van Helsing again). It’s noted for its lesbian undertones, and Holden certainly conveys sapphic intention, particularly when seducing young Lili (Nan Grey), but it’s pretty slow-going. That same year, horror took a hit. Universal was bought by Standard Capital and its founder, Carl Laemmle, was ousted, along with his son. The new owners, dubbing the company “the new Universal” placed far less emphasis on the horror output and it took a back seat for the remainder of the decade.

UP NEXT: WORLD WAR II AND THE HORROR BAN